Name:

|

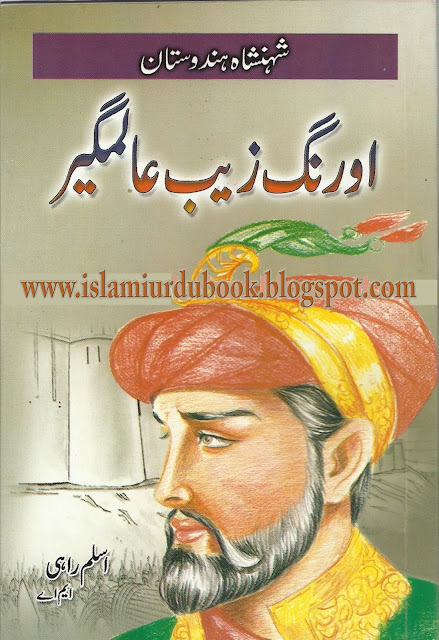

Aurangzeb Alamgir

|

Writer:

|

Aslam Rahi

|

Translation:

|

In Urdu

|

Format:

|

PDF

|

Aurangzeb

|

Aurangzeb on horseback. |

Aurangzeb was a notable expansionist and during his reign, the Mughal Empire reached its greatest extent temporarily. During his lifetime, victories in the south expanded the Mughal Empire to more than 3.2 million square kilometers and he ruled over a population estimated as being in the range of 100-150 million subjects, with an annual yearly tribute of £ 38,624,680 in 1690 (the highest in the world at that time).

Aurangzeb's policies partly abandoned the legacy of pluralism, which remains a very controversial aspect of his reign. Rebellions and wars led to the exhaustion of the imperial Mughal treasury and army. He was a strong-handed authoritarian ruler, and following his death the expansionary period of the Mughal Empire came to an end, and centralized control of the empire declined rapidly.

Early life.

Aurangzeb was born on 14 October 1618, in Dahod, Gujarat. He was the third son and sixth child of Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal. His father was a governor of Gujarat at that time. In June 1626, after an unsuccessful rebellion by his father, Aurangzeb and his brother Dara Shikoh were kept as hostages under their grandparents' (Nur Jahan and Jahangir) Lahore court. On 26 February 1628, Shah Jahan was officially declared the Mughal Emperor, Aurangzeb and returned to live with his parents at Agra Fort, where Aurangzeb received his formal education in Arabic and Persian. His daily allowance was fixed at Rs. 500 which he spent on religious education and the study of history. He also accused his brothers of alcoholism and Nitpicking. [Citation needed]

On 28 May 1633 Aurangzeb escaped death when a powerful war elephant stampeded through the Mughal imperial encampment. He rode the elephant and struck against its trunk with a lance, and successfully defended himself from being crushed. Aurangzeb's Valour was appreciated by his father who conferred him the title of Bahadur (Brave) and had him weighed in gold and presented gifts worth Rs. 200,000. This event was celebrated in Persian and Urdu verses and Aurangzeb said.

If the (elephant) fight had ended fatally for me it would not have been a matter of shame. Death drops the curtain even on Emperors; it is no dishonor. The shame lay in what my brothers did!

Early military campaigns and administration.

Bundela War.

On 15 December 1634, Aurangzeb was given his first command, comprising 10,000 horses and 4,000 troopers. He was allowed to use the red tent, which was an imperial prerogative. [Citation needed]

Subsequently, Aurangzeb was nominally in charge of the force sent to Bundelkhand with the intent of subdue the rebellious ruler of Orchha, solan Singh, who had attacked another territory in defiance of Shah Jahan's policy and was refusing to atone for his actions. By arrangement, Aurangzeb stayed in the rear, away from the fighting, and took the advice of his generals as the Mughal Army gathered and commenced the Siege of Orchha in 1635. [citation needed] The campaign was successful and Singh was removed from power.

Viceroy of the Deccan.

Aurangzeb was appointed Viceroy of the Deccan in 1636. After Shah Jahan's vassals had been devastated by the alarming expansion of Ahmednagar during the reign of the Nizam Shahi boy-prince Murtaza Shah II, the emperor dispatched Aurangzeb, who in 1636 brought the Nizam Shahi dynasty to an end. In 1637, the Safavid princess married Aurangzeb, Dilras Banu Begum, also known as Rabia-ud-Daurani. She was his first wife and chief consort. He also had an infatuation with a slave girl, Hira Bai, whose death at a young age greatly affected him. In his old age, he was under the charms of his concubine, Udaipur Bai. The latter had formerly been a companion to Dara Shikoh , In the same year, 1637, Aurangzeb was placed in charge of annexing the small Rajput kingdom of Baglana, which he did with ease.

In 1644, Aurangzeb's sister, Jahanara, was burned when the chemicals in her perfume were ignited by a nearby lamp while in Agra. This event precipitated a family crisis with political consequences. Aurangzeb suffered his father's displeasure by not returning to Agra immediately but rather three weeks later. Jahanara Shah Jahan had been nursing back to health in that time and thousands of vassals had arrived in Agra to pay their respects. [Citation needed] Shah Jahan was outraged to see Aurangzeb enter the interior of the palace compound in military attire and immediately dismissed him from his position of Viceroy of the Deccan; Aurangzeb was also no longer allowed to use red tents or to associate himself with the military official standard of the Mughal emperor. [Citation needed]

In 1645, he was barred from the court for seven months and mentioned his grief to fellow Mughal commanders. Thereafter, Shah Jahan appointed him governor of Gujarat where he served well and was rewarded for bringing stability. [Citation needed]

In 1647, Shah Jahan Aurangzeb moved from Gujarat to be governor of Balkh, replacing a younger son, Murad Baksh, who had proved ineffective there. The area was under attack from Uzbek and Turkoman tribes. Whilst the Mughal artillery and muskets were a formidable force, so too were the skirmishing skills of their opponents. The two sides were in stalemate and Aurangzeb discovered that his army could not live off the land, which was devastated by war. With the onset of winter, he and his father had to make a largely unsatisfactory deal with the Uzbeks, giving away territory in Nominal exchange for recognition of Mughal sovereignty. The Mughal force suffered still further with Uzbeks and other attacks by tribesmen as it retreated through snow to Kabul. By the end of this two-year campaign, into which Aurangzeb had been plunged at a late stage, a vast sum of money had been expended for little gain.

Further inauspicious military involvements followed, as Aurangzeb was appointed governor of Multan and Sindh. His efforts in 1649 and 1652 to dislodge the Safavids at Kandahar, which they had recently retaken after a decade of Mughal control, both ended in failure as winter approached. The logistical problems of supplying an army at the extremity of the empire, combined with the poor quality of armaments and the intransigence of the opposition have been cited by John Richards as the reasons for failure, and a third attempt in 1653, led by Dara Shikoh, met with the same outcome.

Dara Shikoh's appointment followed the removal of Aurangzeb, who once again became Viceroy in the Deccan. He regretted this and harbored feelings that Shikoh had manipulated the situation to serve his own ends. Aurangbad's two jagirs (land grants) were moved there as a consequence of his return and, because the Deccan was a relatively impoverished area, this caused him to lose out financially. So poor was the area that grants were required from Malwa and Gujarat in order to maintain the administration and the situation caused ill-feeling between father and son, Shah Jahan insisted that things could be improved if Aurangzeb made efforts to develop cultivation, but the efforts that were made proved too slow in producing results to satisfy the emperor.

Aurangzeb proposed to resolve the situation by attacking the dynastic occupants of Golconda (the Qutb Shahis) and Bijapur (the Fair Shahis). As an adjunct to resolving the financial difficulties, the proposal would also extend Mughal influence by accruing more lands. Again, he was to feel that Dara had exerted influence on his father, believing that he was on the verge of victory in both instances, Aurangzeb was frustrated that Shah Jahan chose then to settle for negotiations with the opposing forces rather than pushing for complete victory,

War of Succession.

The four sons of Shah Jahan all held posts as governors during the lifetime of their father. The emperor favored the eldest, Dara Shikoh, and this had caused resentment among the younger three, who at various times sought to strengthen alliances between themselves and against Dara . There was no Muslim tradition of primogeniture and historian Satish Chandra says that "In the ultimate resort, connections among the powerful military leaders, and military strength and capacity [were] the real arbiters." Jacques Weber, emeritus professor of modern history at the University of Nantes, explains that "... the loyalties of these officials seem to have been motivated more by their own interests, the closeness of the family relation and above all the charisma of the pretenders than by ideological divides. "The contest for power was primarily between Dara Shikoh and Aurangzeb because, although all four sons had demonstrated competence in their official roles, it was around these two that the supporting cast of officials and other influential people mostly circulated. There were ideological differences - Dara was an intellectual and a religious liberal in the mold of Akbar, while Aurangzeb was much more conservative - but, as historians Barbara D. Metcalf and Thomas R. Metcalf say, "To focus on divergent philosophies neglects the fact that Dara was a poor general and leader. It also ignores the fact that factional lines in the succession dispute were not, by and large, shaped by ideology ... "Muslims and Hindus did not divide along religious lines in their support for one or nor the other pretender, according to Chandra, there is much evidence to support the belief that Jahanara and other members of the royal family were split in their support. Jahanara, certainly, at various times interceded on behalf of all of the princes and was well-regarded by Aurangzeb even though she shared the religious outlook of the Virgin.

Having made clear that he wanted Dara to succeed him, Shah Jahan became ill with stranguary in 1657 and was closeted under the care of his favorite son in the newly built city of Shahjahanabad (Old Delhi). Rumours of the death of Shah Jahan abounded and the younger sons were concerned that Virgin might be hiding it for Machiavellian reasons. Thus, they took action: Shah Shuja prepared to contest the throne from Bengal, where he had been governor since 1637, while Murad did the same in his governorship of Gujarat and Aurangzeb did so in the Deccan. It is not known whether these preparations were made in the mistaken belief that the rumors of death were true or whether the challengers were just taking advantage of the situation.

|

| Aurangzeb Becomes emperor. |

After regaining some of his health, Shah Jahan moved to Agra and Dara urged him to send forces to challenge Shah Shuja and Murad, who had declared themselves rulers in their respective territories. While Shah Shuja was defeated at Banares in February 1658, the army sent to deal with Murad discovered to their surprise that he and Aurangzeb had combined their forces, the two brothers having agreed to partition the empire once they had gained control of it. The two armies clashed at Dharmat in April 1658, with Aurangzeb being the victor. Shuja was being chased through Bihar and the victory of Aurangzeb this proved to be a poor decision by Dara Shikoh, who now had a defeated force on one front and a successful pre-occupied unnecessarily force on another. Realising Bihar recalled that his forces would not arrive at Agra in time to resist the emboldened Aurangzeb's advance, Dara scrambled to form alliances in order but found that Aurangzeb had already courted key potential candidates. When Dara's disparate, hastily concocted Aurangzeb's army clashed with well-disciplined, battle-hardened force at the Battle of Samugarh in late May, Dara's neither men nor his generalship were any match for Aurangzeb. Dara had also become over-confident in his own abilities and, by ignoring advice not to lead in battle while his father was alive, he cemented the idea that he had usurped the throne. [18] "After the defeat of Dara, Shah Jahan was imprisoned in the fort of Agra where he spent eight long years under the care of his favorite daughter Jahanara.

Aurangzeb then broke his arrangement with Murad Baksh, which had probably been his intention all along. Instead of looking to partition the empire between himself and Murad, he had his brother arrested and imprisoned at Gwalior Fort. Murad was executed on 4 December 1661, ostensibly for the murder of the diwan of Gujarat some time earlier. The allegation was encouraged by Aurangzeb, who caused the diwan's son to seek retribution for the death under the principles of Sharia law. Meanwhile, Dara gathered his forces, and moved to the Punjab. The army sent against Shuja was trapped in the east, its generals Jai Singh and flow submitted to Aurangzeb Khan, but Dara's son, Suleiman Shikoh, escaped. Aurangzeb Shah Shuja offered the governorship of Bengal. This move had the effect of isolating Dara Shikoh and causing more troops to defect to Aurangzeb. Shah Shuja, who had declared himself emperor in Bengal began to annex more territory and this prompted Aurangzeb to march from Punjab with a new and large army that fought during the Battle of Khajwa, where Shah Shuja and his chain-mail armored war elephants were routed by the forces loyal to Aurangzeb. Shah Shuja then fled to Arakan (in present-day Burma), where he was executed by the local rulers.

With Shuja and Murad disposed of, and with his father immured in Agra, Aurangzeb Dara Shikoh pursued, chasing him across the north-western bounds of the empire. Aurangzeb claimed that Dara was no longer a Muslim and accused him of poisoning the Mughal Grand Vizier Saadullah Khan. Both of these statements however lacked any evidence. [Citation needed] After a series of battles, defeats and retreats, Dara was betrayed by one of his generals, who arrested and bound him. In 1658, Aurangzeb arranged his formal coronation in Delhi.

"On 10 August 1659, Virgin was executed on grounds of apostasy." Having secured his position, his frail father Aurangzeb confined at the Agra Fort but did not mistreat him. Shah Jahan was cared for by Jahanara and died in 1666.

Reign.

Establishment of Islamic law.

|

Mughal Empire under Aurangzeb's

period show in red borders.

|

Historian Catherine Brown has noted that "The very name of Aurangzeb seems to act in the popular imagination as a signifier of politico-religious bigotry and repression, regardless of historical accuracy." The subject is controversial and, despite no proof, has resonated in modern times with popularly accepted claims that he intended to destroy the Bamiyan Buddhas centuries before the Taliban did so. As a political and religious conservative, Aurangzeb chose not to follow the liberal religious viewpoints of his predecessors after his ascension. Shah Jahan had already moved away from the liberalism of Akbar, although in a token manner rather than with the intent of suppressing Hinduism, Aurangzeb took the change still further. Though the approach to faith of Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan was more syncretic than Babur, the founder of the empire, Aurangzeb's position is not so obvious. His emphasis on sharia competed, or was directly in conflict, with his insistence that zawabit or secular decrees could supersede sharia. Despite claims of sweeping edicts and policies, contradictory accounts exist. He sought to codify Hanafi law by the work of several hundred jurists, called Fatawa-e-Alamgiri. It is possible the War of Succession and continued incursions combined with Shah Jahan's cultural expenditure spending made impossible.

|

Aurangzeb compiled

Hanafi law by introducing the

|

As emperor, Aurangzeb enforced morals and banned the consumption, usage and practices of: alcoholism, gambling, castration, servitude, Eunuchs, music, Butch and narcotics in the Mughal Empire. [Citation needed] He learned that at Sindh, Multan, Thatta and particularly at Varanasi, the Hindu Brahmins attracted large numbers of indigenous local Muslims to their discourses. He ordered the Subahdars of these provinces to demolish the schools and the temples of non-Muslims , Aurangzeb also ordered Subahdars to punish Muslims who dressed like non-Muslims, regardless of their ethnic backgrounds. [Citation needed] The executions of the antinomian mystic Sufi Sarmad Kashani and the ninth Sikh Guru Tegh Bahadur bear testimony to Aurangzeb's religious intolerance; the former was beheaded on multiple accounts of heresy, the latter because he objected to Aurangzeb's forced conversions.

Another instance of Aurangzeb's notoriety was his policy of temple destruction, for which figures vary wildly from 80 to 60,000. Indian historian Harbans Mukhia wrote that "In the end, as recently recorded in Richard Eaton's careful tabulation, some 80 temples were demolished between 1192 and 1760 (15 in Aurangzeb's reign) and he compares this figure with the claim of 60,000 demolitions, advanced rather nonchalantly by 'Hindu nationalist' propagandists, 'although even in that camp professional historians are slightly more moderate. "Among the he demolished Hindu temples were the three most sacred: the Kashi Vishwanath temple, Kesava Deo Somnath temple and temple. He built large mosques in their place. In 1679, he ordered the destruction of several prominent temples that had become associated with his enemies: these included the temples of Khandela, Udaipur, Chittor and Jodhpur. Historian Richard Eaton believes the overall understanding of temples to be flawed. As early as the sixth century, temples became vital landmarks political as well as religious ones. He writes that desecration temple was not only widely practiced and accepted, it was a necessary part of political struggle.

Francois Bernier, who traveled and chronicled Mughal India during the War of Succession, notes the distaste of both Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb for Christians. This led to the demolition of Christian settlements near the European factories and enslavement of Christian converts by Shah Jahan. Furthermore, Aurangzeb stopped all aid to the Christian missionaries (Frankish Padres) that had been initiated by Akbar and Jahangir.

Ram Puniyani states that Aurangzeb was not always fanatically anti-Hindu, and kept changing his policies depending on the needs of the situation. He banned the construction of new temples, but permitted the repair and maintenance of existing temples. He also made generous donations of jagirs to several temples to win the sympathies of his Hindu subjects. There are several firmans (orders) in his name, supporting temples and gurudwaras, including Mahakaleshwar temple of Ujjain, Balaji temple of Chitrakoot, Umananda Temple of the Guwahati and the Shatrunjaya Jain temples.

Aurangzeb Alamgir Reading Books Online

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1

|

Aurangzeb Alamgir

|

-

|

Pages 98

| ||

Aurangzeb Alamgir PDF Download

| |||||

1

|

Aurangzeb Alamgir

| - |

90 MB

| ||

Aurangzeb Alamgir Zip-Files Download

| |||||

1

|

Aurangzeb Alamgir

| - |

381 MB

| ||

0 comments:

Post a Comment